The Infinite Gallery

A Secret Aesthetic of Quotidian Forms

The ancient Egyptians had no word for art.

I read this fact somewhere in a book whose title and author I cannot remember, nor whether its primary subject was the history of artistic style, or culture, or geography, nor in what context I encountered it. The fact itself has remained with me long after all else about its source has faded away. I have always been struck by the strangeness of the idea that a culture as vast and ancient as Egypt, a culture that produced so many wondrous artifacts of visual and architectural excellence, had no distinct concept of ‘art’ separate from other concepts less concerned with aesthetic excellence, such as economics, warfare and, of course, religion. But does having no word for art equate to having no sense of it? If this sense of ‘art’ wasn’t sequestered away within its own linguistic/conceptual space, as it is for us, then where did it exist? There can be little doubt that the culture responsible for such temples and such walls had a deep understanding of beauty. This leads us to question whether it was the Egyptians who lacked the ability to contextualize their perception of beauty, or is it us who lack some greater understanding?

Is beauty something created, or something perceived?

What if we are surrounded by beauty all the time but lack the kind of sight necessary to see it? What if, hidden within the world, there exists a lost harmony concealed within the chaos of discordant forms, a secret aesthetic? What if there exists a gallery unlike any other gallery, a gallery both immeasurably vast and infinitesimally small, containing within it works of art so sprawling in scale that they cover entire city skylines, and works so small they could fit on the corner of a postage stamp? Works of ephemera made and lost amid the raindrops rolling down a window pane, and works sculpted from mountains by the hands of centuries? A gallery of endless, interconnected rooms without door or wall, a gallery with no entrance and no exit, which you have never entered and can never leave? An infinite gallery where beauty exists everywhere, waiting to be found?

These are the questions that are brought to me by the dollies.

A few notes on the dollies.

The location is a small cabinet factory in the backwoods of northern Georgia, a hot and windowless building where everything is tinted an eternal sepia by a haze of sawdust that remains suspended in the air, and the pneumatic hiss of cracked pressure-hoses is a soft and ever-present sound. Large machines fill the interior of the factory and stacks of wood line the walls. The wood makes its way through the factory along a kind of loose assembly-line, stacks of boards moving from one machine to the next as they are sanded and edged and swallowed whole by whale-mouthed contraptions that cure them via ultra-violet light. At the end the wood arrives at the assembly-section where it is nailed together by large men in sleeveless shirts with beer-bellies and beards, wielding cross-peen hammers in meaty hands with a delicacy that is belied by their coarse dialog and bearish appearance.

In the section where I work stacking boards onto the conveyor belt that goes into the UV-machine, the boards are moved between machines by dolly. The Britannica Dictionary defines dolly as, ‘A piece of equipment that has wheels and that is used for moving heavy objects.’ The dollies that are used here meet this basic definition while simultaneously transcending it in ways that escape easy articulation, ways that hint at the allure of a quiet complexity concealed within an outward simplicity. A subtle beguiling which worries the edges of awareness like moth-flutter fringes a window.

I develop a private fixation with these dollies shortly after taking the job, and I begin a sidelong study of them which will persist throughout my tenure at the cabinet factory. I attempt to create a mental catalog of all the dollies but they are spread out through the entirety of the factory and constantly in motion, revolving like the horses of a carousel along the circular assembly-line as they accompany the boards they deliver from one machine to the next. I never get a fixed count of the dollies and continue to discover new ones after many weeks of working, finding them squirreled away in cobwebby corners or left in the weedy lot behind the factory by inattentive truck-loaders.

They all share a general design. They consist of a small, flat platform made of wood far older than the new boards they are burdened with, old wood dyed not with chemical stain but with a patina of age and dirt and hard-use. Wood not faded so much as worn threadbare by time, and soft in the way unbreakable things can be. Two large, cast-iron wheels joined by an axle are attached to the center of these platforms and bear the majority of the weight placed upon them. Smaller wheels are center-mounted to the outer width-ends and spin along swivel-mechanisms in order to assist with the steerage of the dollies. Thick brackets on the platform corners are embossed with the letter L and the letter R, so that a length of two-by-four can be inserted into them and used as a vertical tiller to guide the dolly as it is rolled.

When unloaded, these dollies are slow and cumbersome and difficult to turn. When carrying hundreds of pounds of boards they are even worse. There is a mechanical, lumbering, old-world quality to them that is at odds with the hyper-efficient ethos of a modern manufacturing facility, where everything is supposed to be streamlined and LEAN. There is an inexplicable aura of the railroad about them, and they conjure images of bindles and hobos, of desolate skylines stained with smokestack twilights, of stow-away journeys through the outskirts of an older world. Camouflaged by the disorder of a busy cabinet factory their uniqueness goes unnoticed, and the more interesting aspects of their nature remain unexamined by most of my fellow workers. The dollies are instruments of simple balance, rolling fulcrums, and wherever balance is key profundity is near. I develop the impression that the soft-spoken significance of form inherent to these overlooked tools speaks to the potential of a deeper integration of the mundane and the marvelous within the fabric of our world, and presents the observer with a conceptual bridge between what is seen as banal and what is seen as beautiful.

I remain alone on the factory floor during break when all the other workers go to the break-room or out in the parking lot to smoke and sit in their cars. I find a box to sit on while eating a vending machine honey-bun and drinking a Mountain Dew, contemplating the mysteries of the dolly.

Is there a way in which the usual understanding of art as something made and sequestered into a separate space, be it a frame or an exhibit or a gallery, does make a gaze defined by false constraints? Is there an unappreciated aesthetic embedded within the layers of modern life that we teach ourselves not to see, folded into quotidian forms?

The Precisionists thought so.

Precisionism is the name used to describe an art-movement that emerged in America in the early half of the twentieth century. Art movements are amorphous things and their lifespans are often subject to debate, but Precisionism is generally agreed to have began in the late teens and ended in the early forties, cradled between the two world wars. Its influences and its impact, however, extend much farther in both directions.

‘Precisionism’ as a term is derived from certain elements of style shared by the artists within this group, repeated patterns and preferences of depiction within the paintings and photographs: strait edges, an emphasis on the geometric forms of modern buildings, a pared down detail that tilts toward minimalism, a clarity and exactness that echoes the uniformity of machined parts. An exclusion of humanity and a love of light. It is a distinct set of qualitative aspects that was not easy to find a term for, as the group were called many things in their own time: the Immaculates, the Sterilists, the New Classicists. Posterity ultimately decided on Precisionism. The exact origin of the term ‘Precisionism’ seems unknown. It is often ascribed to scholars at the Museum of Modern Art who applied it retroactively to a loose-knit group of artists whose work co-existed in time and place and explored many of the same themes, but who never conceived of a shared identity among themselves. According to this theory, ‘Precisionism’, as such, developed as a categorization tool useful in the curation of otherwise uncategorized work. Other accounts claim the term was created and used by some of the artists whose work it applies to, indicating a self-awareness among its practitioners as belonging to, at least, some kind of a vague cohort of like-minded individuals united by certain similarities of style and subject. The truth is likely lost to time, and likely irrelevant.

Precisionism was one of the many radical departures from more traditional modes of representation that exploded in the Modernist period. Emerging from the chaos of Cubism, these movements developed amid this great fracturing of form and with a desire to explore it, a fracturing deeply connected to a rapidly changing world.

Precisionism was in many ways similar to other movements of the time, and in many ways different. It was less dream-like than Surrealism, less overtly political than Dada. Not as kaleidoscopic as Orphism, or as symphonic as Synchromism. While deeply connected to photography, it was not photo-realistic. Precisionism inherited many sharp angles from Picasso and Braque, but its geometry is seldom heavily abstracted. Where Purism reduced shapes in an attempt to distill an intrinsic form, Precisionism transcribed shape in search of a lyrical essence. The Precisionists ignored people and painted light. Less possessed by the ‘universal dynamism’ of the Futurists, the Precisionists were not consumed by a celebratory enthusiasm for the technological changes that the Industrial Revolution and globalism promised to bring, so much as they harbored an aching sincerity in search of a shape. In the absence of castles they painted factories, in the absence of pyramids they painted grain elevators.

This bouquet of ‘isms’ is in some ways as flawed as all other attempts to categorize individuals into groups. The amount of stylistic and subject-matter overlap can make any hard distinction between such movements seem at best academically pedantic and at worst fundamentally artificial. However, I feel that a specific examination of the Precisionists is warranted due to certain unique aspects of their approach to artistic expression and the insights we stand to gain by studying them.

Unlike many of the other groups, the Precisionists had no coherent ideology about art or society. They claimed no goals and wrote no manifestos. Their attitude about art, like that of the Ancient Egyptians, is largely a mystery to be explored.

The main factor distinguishing the Precisionists from their peer-movements, is the fact that they were American. It is a movement of the new world rather than the old, and it took for its subject matter the monuments of modernity. Factories, silos, airplane hangers, skyscrapers. There are no cafes or royal courts, no sunflowers or picnics by the Seine. There are railroad tracks running through sprawling train-yards, and dim cityscapes bristling with smokestacks. Side-views of staircases in landscapes obscurely industrial, and the backsides of buildings seen at oblique angles. In many ways Precisionism is the inverse function of Ansel Adams’ mode of American representation; small scenes of no grandeur.

Some of the names associated with Precisionism would be familiar to you, where the movement overlapped with certain corners of imminent careers: Georgia O’Keeffe, Marcel DuChamp, Edward Hopper. Other names are less known yet more deeply attached to the Precisionist aesthetic: Ralston Crawford, George Ault, Elsie Driggs. The two artists often said to best represent the movement are the two Charles, Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth.

We can know the names, but who were these Precisionists, really? A group, a movement? A manifestation of social trends and forces? A cast of players caught between scenes and writing their own script, navigating the unknown ground between new and old? A secret society of renegade aesthetes searching for lost patterns in the lonesome machinery of modern life?

Lost how? To what…?

Let us explore.

One of the earliest artistic works typically included in the Precisionist oeuvre are a series of depictions of chocolate grinders by Marcel Duchamp.

The image depicts a simple rotary appliance meant for the grinding of cocoa beans into chocolate paste, a miniature melanger common to households in the early twentieth century. Visually, it is a series of circular shapes depicted with a clean-cut straightforwardness reminiscent of a traditional still-life. The fact that the subject of the still-life is a simple machine, a mechanism rather than a flower vase or a fruit bowl, is indicative of the ways in which the Precisionist perspective would shift away from subject matter more strongly associated with an older and more nature-centered world, and toward the machinery that was beginning to dominate the present time.

The image highlights the inter-locking movements of the chocolate grinder in a way that celebrates the elegance of efficient design and the precision required to attain it. The play of light and shadow place the appliance on a level surface unknown to us but solidly within the dimensions of our own world, allowing us to feel its reality, its heft. It is a painting with simple charm that focuses the viewer’s attention on something at that time familiar and likely unnoticed. When we look at the picture we can hear the gentle crunch of the beans beneath the drums and smell the aroma of them with our eyes. The picture is a tiny box of parts, a little mechanism. It holds abstraction at arm’s length, unlike Morton Shamberg’s Mechanical Abstraction.

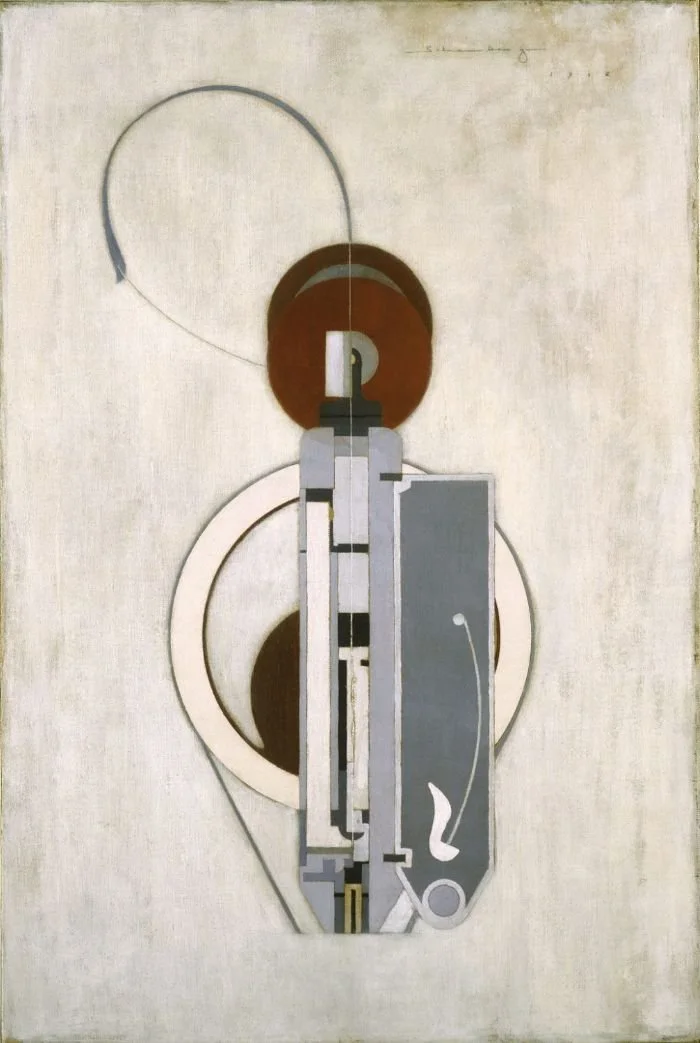

This painting shows a complex mechanical arrangement that strikes the viewer as simultaneously familiar and alien, both everyday and futuristic, combining a sense of disarming regularity and intriguing novelty. It is an indeterminate fusion of components that upon first glance seem mundane, generic, a visual doomed to be lost on a hardware store shelf amid a dozen visuals just like it. Shamberg’s inspiration for the image was an illustration of a wire-stitcher he saw in a trade catalog, but if we lacked this information we would be hard-pressed to apply a specific form to what we see. It could be something from an automobile, a kitchen appliance, an elaborate fishing reel. Whatever it is, it is distinctly modern and distinctly mechanical, a product of a world made of, and with, factories. Shamberg’s image is a representation of the new world, and contains within it all the mystery and exactness of ‘the machine’ as it exists abstractly in our minds. Ripped from the repetitious obscurity of mass production and presented to the viewer as an exulted singularity, it is ‘gadget’ made symbol, ‘gizmo’ made talisman. The painting holds an appreciation for the kind of mechanism that powers and propels everyday life of the early twentieth century, most of which are overlooked and whose intricacies go perennially unappreciated, mechanisms that require a demanding exactness to facilitate their complexity. The painting is a semi-concrete conveyance of the meticulous construction combined with practical application that defined so much of the post-industrial age.

The image is devoid of location, floating in the blank ether of aesthetic concept like a resected organ suspended in a jar of formalin. Though there is no motion, it conveys a subtle ballet of balance, an intercourse of complimentary forms. It is a cold celebration of carefully calculated assemblages and the specificity inherent to the machinery of the modern day. Its structure is emphasized by its isolation from any larger apparatus, and this artificial suspension creates a level of abstraction that clashes wonderfully with the detail of the images’s depiction. Already, in the earliest examples of Precisionism, we encounter strange tensions.

Let us look further.

Paul Strand was a photographer born late in the nineteenth century who would become most well-known for his street-photography and portraits, as well as his attempt to use photography for the advancement of social causes.(One of his most well-known photographs, Blind Woman, combines all of these elements of his career, depicting the heart-wrenching visage of a street-beggar in New York City without the capacity for sight.) However, much of his early work was more formally abstract and centered on modernist subject matter.

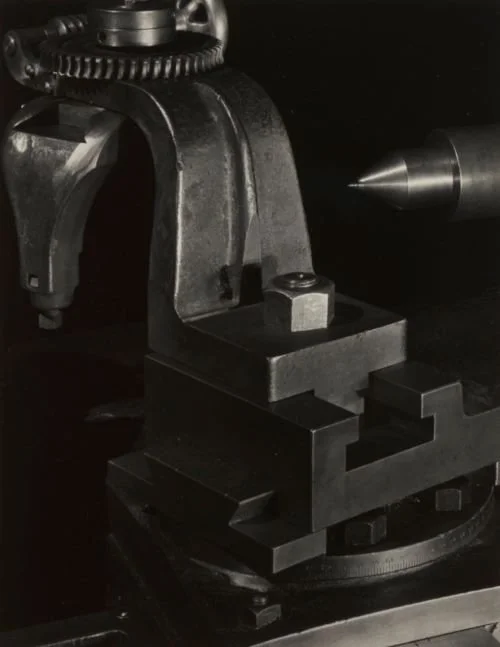

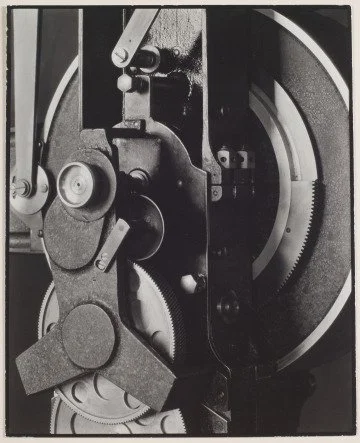

In the early nineteen-twenties, Paul Strand created a series of photographs at the Akeley Machine shop in New York. Photography was an important element in the development of the Precisionist aesthetic, and Paul Strand was one of its most interesting implementers. These photographs of lathes and drilling machines capture what Strand and other Precisionists thought of as the ‘machine aesthetic’, a sense that within the designs of modern machinery there lay hidden an unseen elegance, a cold beauty composed of raw and unadulterated efficiency. A clean, clinical aesthetic tied to the ethos of the era, one of balance, exactness and precision forged in the fires of the steel-mills that made the metal the world was being remade with. The straight lines, the surgical alignment of elements, the rigidness of material and cast; these things spoke to the spirit of the new age, the age of skyscraper and cityscape, highway and factory. There is also something about them that is, while not natural, seems inevitable, inarguable. Every aspect of them is determined by necessity and the dictums of physics rather than the subjective sentiments of man. Strand’s photographs depict things shaped by unthinking forces disconnected from any conscious artistry, like a rock made round by a river. Only the outside forces whose magnitude influenced the design of these machines are not those of nature, but are Invention, Progress, Innovation. The rivers of man’s industry.

Also present within the images is a vague sense of the sexual. The frames are filled with naked steel on naked steel, with the couplings and cominglings of various components. There is the sensuality of chamfered edges, the ‘coming together’ of grooves and gearwheels. The impressionistic resonance of repetitive motions, unseen but felt behind the eyes. Here, lathe and drill are not presented in their entirety but reduced down to subcomponents, isolated from the larger apparatus with a fetishistic focus, like closeup shots of genitalia. See the phallic protrusion at the top right corner of Lathe, and the mounded curve of metal directly across from it more than slightly reminiscent of a vulva. The lower half of the photograph is a busy mess of bolts and blocks and discordant angles which conjures the intimate intricacies of feminine interiors, a cubist invocation of the female undercarriage. This labia-like collection of overlapping surfaces and slotted space reminds us we are peering into the reproductive organs of modernity, and our eyes finger it with wonder and curiosity. We feel a mysterious pull from these images as strong as any lurid picture. Like the vagina, the lathe is both fascinating and confounding, containing within it the elusive possibility the mind senses among the mystery of hidden parts and penetralia. Long hallways and parted legs. (See also Paul Outerbridge)

However, one of Paul Strand’s most iconic photographs has nothing to do with machinery at all.

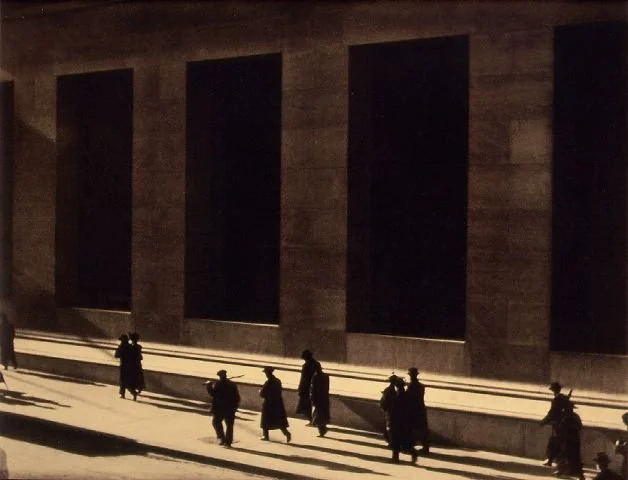

Wall Street, 1915, depicts a random moment of foot-traffic on the sidewalks of New York City, at some soft and transitional part of the day. The center of the photograph is dominated by the wall of a building that runs parallel to the sidewalk, and more strikingly, the massive rectangular openings in the wall that loom over the people passing below. The pedestrians at the bottom of the photograph are small and without feature, clad in coat and hat, facing away from the camera as they walk. They are moving through slanted light that is either the first rays of dawn or the last rays of dusk, heading toward their offices and office-tasks or away from them, though the viewer does not know which.

The presence of the openings is surreal, as their architectural function is unclear to the viewer. They stand as gaping voids, arbitrary and awesome. A repetition of rectilinear shapes that conjures thoughts of the obelisks and totems of older worlds. A colonnade of shadows one might have found deep within the cult-temples of ancient Egypt. Like an open grave, or an unshuttered window at night, they hold a darkness full of the unknown, and speak of great depths haunted by what might be and what might not, monolithic and inscrutable.

The pale stone, the inner shadows, the aching precision of ancient crafts. The image is an ashlar echo of an older world, one ruled by gods and goddesses long since forgotten. The building in the image is a shrine to the new gods that have arisen to replace them, forces just as rapacious and universe-shaping as the sun gods and dog-headed psychopomps that ruled over antique sands. Capital, profit, business. There is an alchemy within this photograph, an eon-spanning transformation that has unfolded within the minds of men; Luxor become J.P. Morgan, Ra become ROI. A temple of modern cosmology, a new shrine in a new desert.

The image is both nondescript and picturesque in a way that evokes the anonymous energy of a modern city. It holds a beguiling duality, a synthesis of the mundane and marvelous, an aesthetic discordance that contains divergent worlds. It captures both the ephemeral texture of everyday life as well as the more resonant reverberations of archaic concepts, overlaying them in the viewers mind like dissonant tones played simultaneously on the same instrument. This deep yet subtle clash evokes in the viewer something hard to define, an atonal throb within the soul. More strange tensions. Within this beige and faceless photograph there resides some unspeakable quality of apprehension caught between the prosaic and the profound, connected in grand and opaque ways to the beauty that hides between unnoticed moments and in unexamined spaces. The secret and radiant everything that true art teaches us how to see.

Here, we do not see the Infinite Gallery, for the Infinite Gallery is too omnipresent to be seen, being no shape and all shapes simultaneously, being everywhere and nowhere at once. We sense it, though, we feel its conceptual presence. We understand that this photograph is a an open door into a certain way of seeing, into a mode of interacting with our own existence that acknowledges the unnoticed beauty all around us, hidden in plain sight. This photograph is a map to treasure buried in our own backyard, a password into a hideout which we are already inside of. It is a half-seen glimpse of something strange and exultant, something we almost remember, but then lose amidst the shuffling of shadows beneath our thoughts.

Photography was used by the Precisionists to explore many of the same themes as the paintings examined: the oblique beauty of the urban landscape, the hidden elegance of geometric forms within modern architecture. The grandeur of Industry and all that it has birthed: bridges, factories, skyscrapers.

Perhaps the best example of this overlap are the photos taken by Charles Sheeler at River Rouge.

Charles Sheeler was one of the most influential and well-known of all Precisionist artists, working prominently in both painting and photography. He created some of the most iconic of all Precisionist imagery, and along with Charles Demuth, is responsible for shaping much of the aesthetic that has come to be associated with the group (see: American Landscape 1930, Upper Deck 1928, Water 1945). Sheeler also had commercial endeavors which he pursued in order to to support his more avant-guard work. He was employed by various magazines and advertising agencies, and it was an assignment from one of these last that sent him to the River Rouge manufacturing plant in 1927 to photograph it for the Ford Motor Company.

Located outside of Detroit Michigan along the waterway it was named after, the River Rouge Plant was a vast, sprawling labyrinth of large-scale industrial production dedicated to making early automobiles such as the Model A and the Model B. At 2,000 acres, it was the world’s largest factory, and as the first to produce and assemble every component of a vehicle at one site it was a groundbreaking experiment in vertical-integration and one of Henry Ford’s most significant manufacturing innovations. It was the Ford Motor Company’s flagship facility, and a manifestation of the nation’s love for machine, motor, and mass production, the holy trinity of what Sheeler described as America’s ‘substitute for religious experience.’

Sheeler wasn’t the only artist to be inspired by the River Rouge Plant. Charlie Chaplin is said to have visited the factory before filming his cinematic masterpiece Modern Times, and the assembly-line scenes in that movie are credited by many to have been inspired by the working conditions he saw at River Rouge. Diego Rivera famously depicted the facility in a mural at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Where Rivera’s depiction is highly stylized and focuses on the elements of group-effort and human collaboration, Sheeler’s photographs are almost entirely devoid of human presence. Sheeler depicts a world of uninhabited spaces filled not with the dynamism of collective labor, or the future-fetish of technology-worship, but with the cold grandeur of industrial architecture. His photos are almost exclusively of the buildings and machinery that make up the plant, unencumbered by the presence of humanity. Smokestacks rise against gray skies like slender towers. Massive contraptions of girder and beam stand like skeletal monuments to something unnamed and forgotten. Blast furnaces stand beside motionless waters like primitive castles beyond a moat. Dirt roads lead deeper into the labyrinth, tattooed with the cross-hatched lines of shadows falling from above. Mounds of ore look like rows of featureless ziggurats in a barren landscape. It is a world made of anonymous buildings and slanted conveyors, foregrounds filled with massive tanks and ramshackle warehouses, distances cluttered with chaotic detail.

The structures of the plant are examined with a clinical detachment that neither attempts to glorify them nor demonize them, only depict them as they are and without commentary. Structure in the abstract. This detachment allows the infrastructure of the plant to be defined by its own intrinsic qualities, the curves, the angles, the strait lines. The inherent stateliness of design rooted in function and stripped of all ornament. They are analogues to the Strand photos depicting close-up shots of machinery, only expanded outward. The same fixation on mechanical function, on parts and pieces of a machine, only this machine is the size of a small city. This is a machine that swallows humans and allows them to get lost within its strange interiors (the way Chaplin was swallowed in Modern Times?). They share many qualities: the reduction of extraneous elements, the isolation of components within a whole, the naked elegance of industrial arrangement. However, Sheeler’s photographs of River Rouge contain something that Strand’s closeup shots of a lathe do not. There is a quality to these photographs that one finds in almost all Precisionist art, but which seems more concentrated here for reasons both subtle and elusive. There is a visual silence within the imagery that creates an unintentionally haunted quality, a stillness akin to the pallid calm of ghost-towns and abandoned amusement parks. An ethereal quietude that holds within it something sweetly forsaken, an awful, aching purity that feels like an echo of some secret emptiness that exists at the center of our deepest selves. A vast aloneness that is somehow both outside us and within, wide and vacant, extending in all directions and beyond the borders of the soul. These photographs offer a presentation of the world based on pure aesthetics, not one alive with the presence of people. A vision of the world made by man, rendered clear and uncanny by man’s absence. Click the link to the Library of Congress website and scroll through the photographs, gazing into each one, while sitting in a quiet room where you can be alone. You can feel the empty rooms, taste the soundless air, imagine the miniature sound of your own footsteps as you walk between immense, sleeping machines whose function is unknown to you. Imagine the wonder of being lost in an empty world.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.mi0639.photos/?sp=1&st=image

One of the most iconic images of Precisionism was inspired from this set of photographs.

‘Criss-Crossed Conveyors’ depicts a scene from the River Rouge Plant filled with an almost overwhelming amount of detail. It is a riot of overlapping angles and adjacent shapes that spill into each other in chaotic profusion of intersecting industrial elements. The eye jumps around in search of an unimpeded line of sight and, finding none, retreats and reaproaches each element one at a time.

The image is difficult to navigate as it is obscured by its own visual abundance. The center is dominated by the titular intersection of two conveyors that form a massive cruciform shape which seems to hang suspended in the air over a tangle of smaller walkways. Behind this are more conveyors partially obscured, which in turn obscure the water-towers behind them, which in turn obscure all but the topmost parts of the smokestacks that rise in the distance.

The initial impulse of the viewer may be to look away and escape the visual overload, but the image has a certain draw which the eye cannot ultimately resist. Once the initial haze of confusion wears off, the din of contradicting elements coalesces into something softer and more unified, the excess becomes elegance, the clash becomes unity. The components of the picture seem almost to shift before the viewers eyes from a scatter-plot of hard-angled corners and renegade rectilinear planes, into a kaleidoscopic assemblage of Precisionist excellence. Here we have all the hallmarks of Precisionist imagery: clean lines, geometric shapes, rigid structures, a focus on the overlooked and a marked absence of humanity. The beautification of the unseen. This picture encapsulates the act that Baudelaire described as the task of the modern artist, to ‘find the marvelous in the banal.’ Like all great Precisionist works it is, for the viewer, an exercise in learning how to see. It takes one random perspective from one random place in one random factory, and forces the viewer to see just how much beauty is truly there. How many plant employees walked by that spot every single day and never realized they were moving through a masterpiece? How many Criss-Crossed Conveyors does the average person pass by in their lives without even noticing?

Let us move from a machine the size of a city to a city that moves like a machine.

Manhatta is a silent short film made in 1920 by Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand. It is an attempt to paint a portrait of the city by piecing together random views of Manhattan at different locations and times of day, presented as a study of the ‘Modern Babylon on the Hudson’. The film’s original negative was lost to time, but a digitally restored archive version can easily be found online (see below). It is twelve minuets long and has no specific characters or narrative arc, just shuffles from shot to shot in a loose series of scenes. A ferry full of people, crowded streets, skyscrapers and skylines. The scenes are inter-titled with quotes from Walt Whitman’s Mannahatta, a poem about the city that shares the film’s sense of vibrancy and motion. ‘City of the world (for all races are here), city of tall facades of marble and iron, proud and passionate city.’ ‘Where million-footed Manhatta, unpent, descends upon the pavements.’

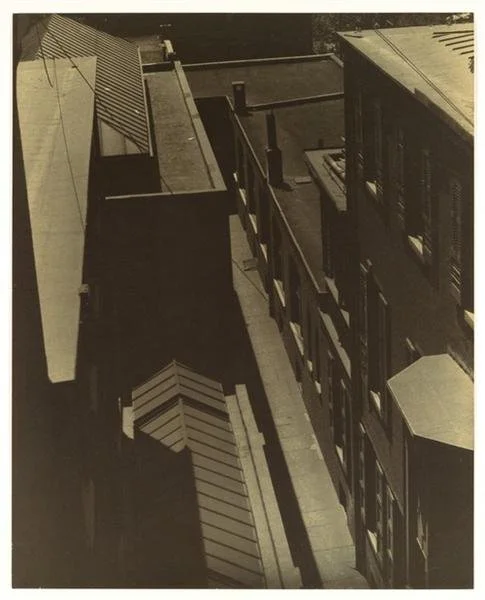

There are no hanging gardens in this Babylon, but splendor abounds. One of the earliest shots is familiar to us as it is the same angle on the same building as the Paul Strand photo, Wall Street, only presented with motion. The inclusion of this iconic shot is ingenious, as it allows us to recognize the Precisionist aesthetic in many of the films following shots. Here we see possible paintings lurking in almost every scene. Watch the film below and pause it at almost any moment, and the still-shot can easily be imagined as a Precisionist painting. Steel beams rising against a gray sky. The sides of buildings seen at tilted angles. A rooftop forest of chimneys bleeding smoke in fat white plumes, the screen half-obscured. Trains passing vacant lots flanked by blank brick walls (another familiar scene, see Charles Sheeler, Church Street L, 1920).

The film is an energy-scape, an attempt to capture the force of life and motion that animates a modern city, the bright fire that fuels it. Portrayed as a symphony of smoke and steam, a mosaic of massive movements, trains, ships, cars, people, Manhattan is a giant machine always churning, spinning, shining, roaring in the stoic silence of black and white film.

The film exists in, and in some ways embodies, a moment of transition between mediums. Painters were becoming photographers who were becoming filmmakers. Here we have a collaboration between one painter/photographer and one photographer/filmmaker, to create a non-linear experiment in visual/textual storytelling that is both expressive and realistic. It takes for its subject a city too massive to fit in a thousand scenes, too multiform to claim a single shape. The film Manhatta, much like the photograph Wall Street, captures the city’s anonymous energy, the synchronic existence of crowds, all-powerful and momentary. The sky-cracking stature of gravity-defying architecture, like concrete ladders to the stars. It attains the removed perspective of a painting that reduces its subject down to outline and structure, while shifting constantly in a tapestry of small movements, like a city’s reflection on a river. We see it with a bird’s eye, and yet feel the vibration of distant locomotion.

Manhatta feels more like an experiment in combining photography and motion than it does an actual film. It is a dance of off-beat angles, a vision of a vanished world. It is as brief and unstructured as a dream, as filled with shadows and pockets of deep space, rippling vapors and undefined distances. The people are small and faceless, the vistas grand and sprawling. It seems in some ways the disassembly of a city, floating through the ether of the American vision, timeless and without bound. A vision that holds within it the shifting of worlds. Not a Babylon, but some grander and less-real Paradise.

Another Precisionist who understood America’s fixation on industry as a secular substitution for religious experience was Charles Demuth. Not a photographer like Strand and Sheeler, Demuth was a painter who specialized in water-color and oils. (What is likely his most well-known painting is an illustration of an imagistic poem by William Carlos Williams, I Saw the Figure 5 In Gold 1928, wherein he depicts the number 5 several time in the antiquated style in which it was painted onto the side of fire engines. It is a combination of exact numerical representation and a hallucinogenic superimposition of forms that capture the rushing vision of the poem marvelously, so much so that when looking at the painting one can feel the billow of air as the fire-engine passes by, hear the scream of the siren, smell the rain of a city night. The painting recreates the sensation of a vision flash-burned onto the eyes, lingering half-made for half a moment.[This is not the only time Demuth took inspiration from poetry. His final oil painting depicts a cork factory, After All (1933), and its title is taken from the Whitman line ‘after all, not to create only.])

The two most interesting of Demuth’s paintings in my opinion are Incense of a New Church (1921), and My Egypt(1927). Both explore the transition away from traditional modes of meaning that existed in the classical world and examines what modern man has replaced them with.

Incense of a New Church is a beautiful, semi-abstract cityscape done in oil. True to Precisionist style, there is no depiction of the people who built the city or who live in it, only the structures that form it, and those exist only in outline. In the center of the picture stand smokestacks that rise from factories we see only obliquely. Both smokestacks and factories are devoid of detail, rendered down to flat black silhouettes that bleed into each other, like simple shapes filled with night. The sky in the background is presented in a series of geometric panels, like a turquoise puzzle pieced together, adding undertones of cubist anti-form. The foreground is dominated by pale, roiling vapor that is either smoke or steam produced by the factories, billowing upward in a wave of white coils that enshroud whatever else might be present in the picture. The vapor is both serpentine and marmoreal, twisting between smokestacks like ivory ribbons, elegant and all-consuming. The ghost of a street-lamp stands half-obscured by the vapor, a half-shadow illuminating the smoke/steam from within, like a lantern in a cloud of fog. This element of the picture is somewhat of a departure from the clean and rigid shapes that occupy most Precisionist pieces, including Demuth’s own. It is almost post-impressionistic, calling to mind certain skies in southern France. It has the flowing quality of water, coursing through the rigid shapes of the smokestacks and toward the turquoise sky like currents of a river passing between stones on its way to the ocean. It is the life-breath of the city, an energy moving through everything. It is the sacrament of a world that has replaced cathedrals with smokestacks, and looks to the its factories for signs and wonders.

Bridges and ferries and bills of sale.

Blood and fire and billows of smoke.

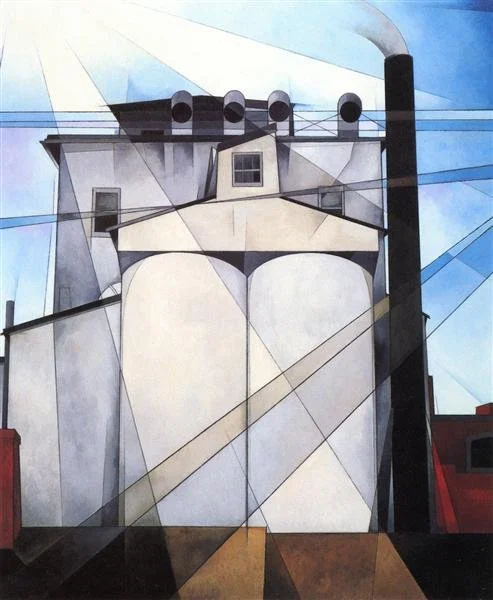

My Egypt is one of Demuth’s most well-known paintings and often cited as exemplifying the the core stylistic values of Precisionism. It depicts a scene from Demuth’s hometown of Lancaster Pennsylvania, and contains a sight that would have been very common in that corner of the world, a grain elevator at a feed mill. The building itself takes up the bulk of the painting and is presented in a clean and straightforward manner, utilizing the calm shades and hard lines of the Precisionist aesthetic. It is overlaid with intersecting beams of light depicted as slanted panes of different colors, so that the entire painting is segmented and somewhat off-balance visually. It retains its crisp and level design while simultaneously breaking down the forms at a structural level, creating a soft sense of dissonance in the viewer’s mind. Realism with a wash of Abstraction.

The beams of light emerge from a kind of burning blankness in the upper corner of the painting that is understood to be the sun. The light evokes the falling lines of certain Egyptian carvings that show the sun, conveying not only light but power and divinity. Placing a structure of common utility within this waterfall of divine illumination forces the viewer to not only see the grain elevator in a different way, but the modern world in its entirety. Can one behold the workaday structures of modern America with the same depth of wonder as the people of the ancient world had when they gazed upon the pyramids of Giza, or the Colossus of Rhodes? Do the triumphs of industry and machine equal the accomplishments of sculptor and pharaoh? If not, why not? The painting makes us wonder if all the beauty and mystery of ancient Egypt are present in the modern world, hidden unseen around us all the time, overlooked. Lost amid the chaos of cars, commercials and thunderous inanity. Is it possible, through the pursuit of a secret aesthetic, to become aware of these unseen qualities, to learn them like a hidden language? Demuth’s painting is a bold declaration, the manifestation of an independent mind rejecting the prescribed sentiment of a society in some ways defined by shallow perception. In an act of artistic rebellion, he is making magnificent what the world wants us to believe is irrelevant, unremarkable, unworthy. Within this painting is a profound insight that flows through the entire body of Precisionist art, an understanding that beauty and utility are not only not mutually exclusive but fundamentally connected in ways so deep and subtle they defy man’s capacity to understand them. A notion that the classroom teaches many things good and bad, how to see and how not to see, and that life is just as much about unlearning as learning. The shedding of limitations and the expansion of limited kinds of sight. My Egypt captures the moment of epiphanous clarity when one realizes that the possibility of beauty extends beyond the borders that one once believed contained them, that meaning and wonder lay all around us in places we never thought to look. That all lighthouses are of Alexandria, that the shadow of the sphinx falls in a small town in Pennsylvania.

One of the most compelling aspects of Precisionist art is also perhaps its most difficult to describe. There is an element throughout most Precisionist painting and photography that conveys a profound sense of isolation, as though the scenes being depicted existed in a world without life, a dream-world of endless and empty spaces occupied only by random buildings with doorless walls, where shadows fall but never move, trapped forever in the amber of an unnoticed hour. There is within this world the ache of solitude, a sweet and simple melancholy that tilts all things inward. Hopper would later perfect this element and place his people within it, adding a humanity to the emptiness that Precisionism lacks, and in so doing give his viewers a reference point to anchor their perspective, a representative in the nothing. Precisionism offers a less diluted emptiness, less palatable perhaps, but more potent, more pure. The emptiness depicted by Precisionist works often overwhelms the structures that the Precisionists try to fill it with. In the attempt to eliminate all extraneous elements and isolate the buildings and bridges and machinery in order to allow the beauty of their design to be understood, many of the works create a kind of vacuum, a void that has more presence in the viewer’s mind than the artifacts attempting to be examined. I believe this element is alienating to many viewers and the primary reason why people who don’t like Precisionist art don’t like it.

In George Ault’s Hoboken Factory (1932), the factory itself fills the painting from one edge of the canvas to the other, a heavy bulk of hard angles whose edges bleed into the darkness of night, its middle parts illuminated by the soft glow of an off-center streetlight. The building is a mosaic of rectangles: its bottom part is lined with rows of dark windows, its upper glass section a crown of turquoise tessera the same color as the twilight sky. A single smokestack emits fumes indistinguishable from the blanket of dark clouds that fill the background of the canvas, so that the factory seems to merge into the landscape rather than exist as something completely separate, woven into the fabric of the image. The foreground is filled with the intersection of two empty streets emerging from the darkness at the edge of the painting, their emptiness illuminated where they meet in front of the streetlight. Taken all together the painting is a simple nocturn made of layered shadows and smoldering light, a nighttime snapshot of a slumbering factory and deserted streets. The elegance of the structure is presented in a clean and understated way that conveys to the viewer a sense of Precision and modernity, as I believe was Ault’s intention. However, at a deeper level, it evokes things less easily articulated - the lovely melancholy of empty rooms with dark windows, the sweet sorrow that grows like a wild vine in the places past the outskirts of cities. The vast unknown that enshrouds all human endeavors. The unspeakable allure of backroads and side-streets and poorly-lit places in the wilds of a rain-gusty night. The way you can only ever feel at home when you are alone. Desiderium Ignotum.

I think of this element of Precisionism as a Sublime Vacancy. The unintentional representation of some inarticulate quality in modern life that defies representation. An examination of something not there. This sublime vacancy is the great and secret subject matter of all Precisionist art, a manifestation of the movement’s collective unconscious. This exists beyond the outer elements of style and technique that align across the movement (clean lines, geometric shapes, absence of people, etc.), in the places of the painting one knows through feel rather than through sight. This is art performing its highest function; the expression of the inexpressible. Within the paintings of empty streets and deserted factories and lonely train-yards are things too large and unknowable for even the most abstract of abstractions, things too real for the most clear-eyed realism. A peculiar emotional frequency found in the foggy halos of light and fog that form around streetlamps in the a.m. wasteland of an abandoned industrial park.

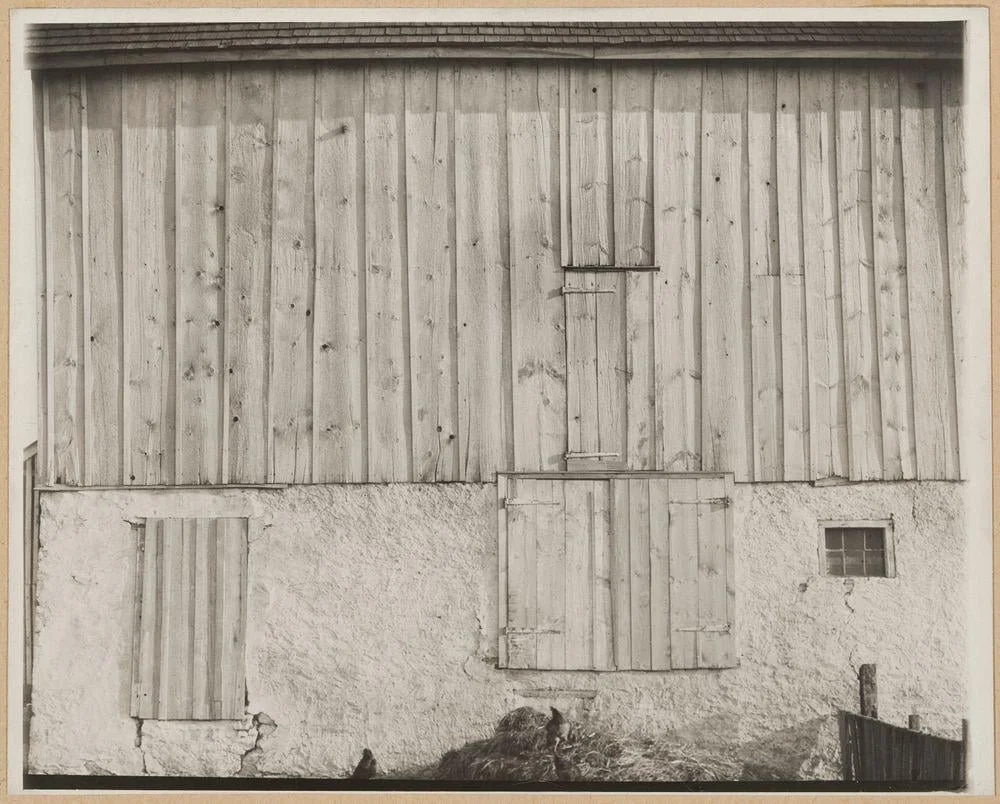

I believe this element of sublime vacancy, and the subtextual attempt to explore it, produces one of the most profound dynamics of all Precisionist aesthetics, the creation of a liminal space between the objective and the subjective that much of Precisionist art exists in. It is a space not named or clearly defined, stranded between the urge to mirror the world accurately and impartially, and the need to portray it in a manner that reflects the artist’s own personal experience. The Precisionists are constantly pulled between the two approaches, never fully embracing or eschewing either, incorporating and abandoning elements of both, hovering in the ill-defined in-between. This deep ambivalence is beyond doubt the source of many of the strange tensions that stretch through Precisionism, like cello strings tuned to an unknown frequency. Precisionism, attaining neither the mimetic restrictions of realism, nor the unrestrained detachments of abstraction, is a movement both mired in and liberated by conceptual liminality. Like all liminality this aspect of Precisionism is both alienating and alluring at the same time, disconcerting us with its nebulosity and seducing us with its strangeness. Never have smokestacks been so generically flat and gothically imposing as they are in Elsie Driggs Pittsburg (1927). Never has the world been as simultaneously over-reduced and expansive as Ralston Crawford’s Overseas Highway (1940). Never has the side of a barn been such a stage for the battle between the mundane and the infinite as Sheeler’s Side of White Barn, Bucks County, Pennsylvania(1917).

This quiet clash of competing perspective extremes creates within the viewer the sense of a tightrope being walked, of a pendulum in mid-swing. Precisionism in many ways was a search for balance in an imbalanced world, an internal transition from one way of seeing into another. A moving mechanism with the old way on one side and the new way on the other, teetering on either side of strange tensions.

Precisionism is a song of the unsung, an attempt to valorize the anonymous, to celebrate the unseen. After sufficient exposure to Precisionist art, one develops the habit, whether desired or not, of seeing Precisionist scenes everywhere. You will be walking down a hallway or through an empty parking lot, or looking at the reverse side of world-facing building, and suddenly, at just the right convergence of angles, the scene before you takes on the quiet, clear cast of a Charles Sheeler photograph, or the oddly-compelling and disturbingly familiar flatness of a Ralston Crawford painting. In these moments the foolish among us, such as myself, may try to capture that aspect of their environment with whatever recording mechanism is closest at hand, be that camera or sketchpad. In these moments one may be filled with a sudden sense of kinship with the Precisionists of old, as though partaking somehow in the same grand endeavor, joining in the same quixotic grasp at some beautiful and unattainable expression. The sense that you share with men and women dead and gone the same painful ache in the soul calling out for a shape. Seeing the fruits of these misguided impulses only serves to reinforce the quixotic nature of such pursuits, and deepens the respect one has for true artists and their ability to engage with such lush ambiguities.

However, once one becomes aware of the Infinite Gallery, one can never escape it. An alleyway is never just an alleyway, a street-lamp is never just a street-lamp. Beauty is everywhere, embedded within the secret aesthetic of quotidian forms, and it becomes something not which one sees, but something which one cannot escape. To discover the Infinite Gallery is to make oneself a prisoner of interminable glamor. It is a labyrinth of twisting charm, and like all labyrinths, contains madness and wonder.

Maybe one function of studying Precisionist art (its most secret and transgressive of functions) is to allow the viewer to see the artifice in categorical constraints when perceiving beauty. Maybe, in some sense, the purpose of studying a Demuth is to better see the ballet of light and shadow beneath a bus-stop streetlamp at 7:15 on a Wednesday night. Maybe there are certain corners of Niles Spencer that, if peered into deeply enough, will transform the half-dried shadow-crescents of stained cocktail napkins into misplaced splinters of seascape, or pocket-sized pieces of stormy sky. Maybe Precisionism is a window into a broader perspective from which we peer out of and see the world in a different way, a many-sided mirror reflecting much more than it shows.

Precisionist artwork holds the secret lesson that all schools fail to teach; that the distinction between the classroom and the playground is an illusion. This lie, hidden inside the structure of the world, is the doorway into the Infinite Gallery. Embedded within the patchwork oeuvre of Precisionist imagery is the conceptual essence of this idea, the idea that beauty can and does exist beyond the boundaries of the frame and outside all attempts of style and technique to capture it. The notion that within the corners of neglected rooms, in the breathless silence of empty halls, there are the materials needed for the mind to perceive beauty if properly open to its possibility. Precisionist beauty is a particular kind, the kind of barren beauty that haunts empty parking lots and the backsides of abandoned office buildings. The beauty of sun-faded colors arranged by the rain in nameless shapes. The beauty of forgotten boxes in sideways stacks and empty streets and sleeping gearwheels. The beauty of blunt architecture, distracted design, and urban sprawl unfurling beneath a starless sky. The beauty of an ugly world.

There is an overlooked artistry in the world created by arbitrary forces and framed within the precision of a machine-produced landscape. Steel towers soaring toward a gray nothingness, concrete buildings, spillways, underpasses. The quiet elegance of unnoticed things. Is the search for this overlooked artistry a thread stretching across time and place and connecting us to the seekers of an older world? Dare we ask what the stone-masons pondered when contemplating the dollies at Denderah? Did Pythagoras learn more from the Egyptians than just Geometry? Does an implicit understanding of this secret aesthetic of quotidian forms explain why the Egyptians had no word for art, that perhaps they had no need for one?

So go my thoughts as I gaze upon the dolly, itself a moving mechanism of balance and transition, itself unseen and beautiful.

The alarm buzzes on the wall signaling the end of break, and my fellow workers begin to make their way back onto the factory floor. My honey-bun is gone and my Mountain Dew can is empty, and my half-hour of undistributed contemplation is over. I take one last look at the dolly and feel a quiver run through my mind, a quiet, internal shaking like a gust of sudden rain rushing through me, a rippling filled with toolbox textures and shipyard shades and all the mysteries of Shaker forms. A soft reverberation pulsing through my innermost self and flowing outward into the unmapped vastness of unnoticed spaces, and down the never-ending halls of an infinite gallery that exists all around us at all times.