Stones, Bones and Basement Wonders

It was in Franklin North Carolina that I decided to take my first zero-day.

For those unfamiliar with trail-terminology, a ‘zero-day’ is a twenty-four hour period specifically set aside by a thru-hiker for rest and physical recuperation, wherein 0.00 trail-miles are hiked. When and where to take zero-days are up to the hiker’s discretion, but it is almost always somewhere in a town where there is access to food, amenities and comfortable sleeping arrangements. I decide to take mine while staying at Baltimore Jack’s, one of the most famous hostels on the southern section of the Appalachian Trail.

A rundown and sun-faded old building, the hostel is named after a renegade trail-bum who completed the trail seven times while carrying Jack Daniels and cigarettes in his backpack. Baltimore Jack had taken his trail-name from the lyrics of a Bruce Springsteen song, ‘I got a wife and a kid in Baltimore, Jack, I went out for a ride and I never went back.’ This is fitting source material for a trail-name not only because it reflects the actual situation of Baltimore Jack, who left his wife and child behind to live a life on the trail. It is also appropriate because it conveys the desire for a new existence that spurs many hikers onto the trail in the first place, and glorifies the beatnik desertion of workaday obligations that many people both detest and secretly dream of. The desire to cast off the bonds of social commitment has undoubtedly been a primary motivation for many people seeking enlightenment by journeying into the wilderness, only many aren’t as honest about it as Baltimore Jack. In the spirit of this legendary trail-bum and his rebellion against responsibility, I decide to indulge my sedentary desires and spend a day off-trail wandering around Franklin.

Part of my motivation to hike the A.T. was to see the small towns of Appalachia, the kind of place where I am from and have always had an affinity for. There is a certain feeling you get from these towns that is some combination of cultural vibe and visual aesthetic, a rough and off-center charm comprised of backwoods eccentricity and industrial decay. The kind of places where you meet story-telling strangers in gas-station parking lots, and see small children playing made-up games in the shadows of abandoned buildings covered in vines. I wanted to take a whole day to soak Franklin in, not just a few tired hours between trail-shuttles.

Early in the morning all of the hikers convene outside Baltimore Jack’s, waiting for the morning shuttle to take them back to the trail. Cajun is there, a bearded hiker I met from Louisiana whose trail-name origin becomes obvious once he speaks.

“Check out the hiker box yonder-way,” Cajun says in a thick bayou twang, “they got a shit-ton of stuff.”

The hostel’s shuttle-vehicle is an old minivan from the eighties, and it fills up with so many hikers that one of the workers literally has to cram the bodies in and shove them together to get the door closed. Cajun has to climb into the very back of the van and scrunch into a ball so the trunk can be shut. Once full, the van wheezes off down the road sunk low on its shocks, the fuzzy smudge of Cajun’s face smiling from the back window, amused at the ridiculousness of it all.

I set out on my exploration.

One of the buildings closest to the hostel is a gem and mineral shop which sells high-dollar jewelry. At first it seems like the kind of place that has nothing to interest a thru-hiker, and the kind of place not thrilled at having disheveled bums taking up space in their store. However, there is a sign painted outside the building advertising a free museum in the building’s basement, and since it is the kind of day for exploring basement museums, I go inside. I pass the jewelry showroom and descend through a short hallway to the bottom of the building.

The room I enter is small and brightly lit, and absolutely filled with glass display cases. Cases line every wall of the room from floor to ceiling, and rows of long, glass-fronted cabinets fill the center of the room with narrow aisles between them. All of the cases are crammed with minerals and artifacts, each with a small information plaque describing it. There is no-one else in the room when I arrive, and I move around slowly and without speaking, peering through the glass, amazed.

Hundreds of stones, skulls, fossils and sculptures have been laid out on the shelves in a lavish array of curiosities that somehow seem to sprawl even in such a small space. The shelves literally teem with things, and every available surface is covered with an abundance of artifacts. It is all sufficiently well-presented so as to astound the viewer with variety while not disorienting them with profusion. This creates a marvelous sense of immersion, and I feel as though I have stepped into a small cave filled with lost treasures arrayed around me.

Despite the sign outside, this small room isn’t so much a museum as it is what used to be known as a Wunderkammer.

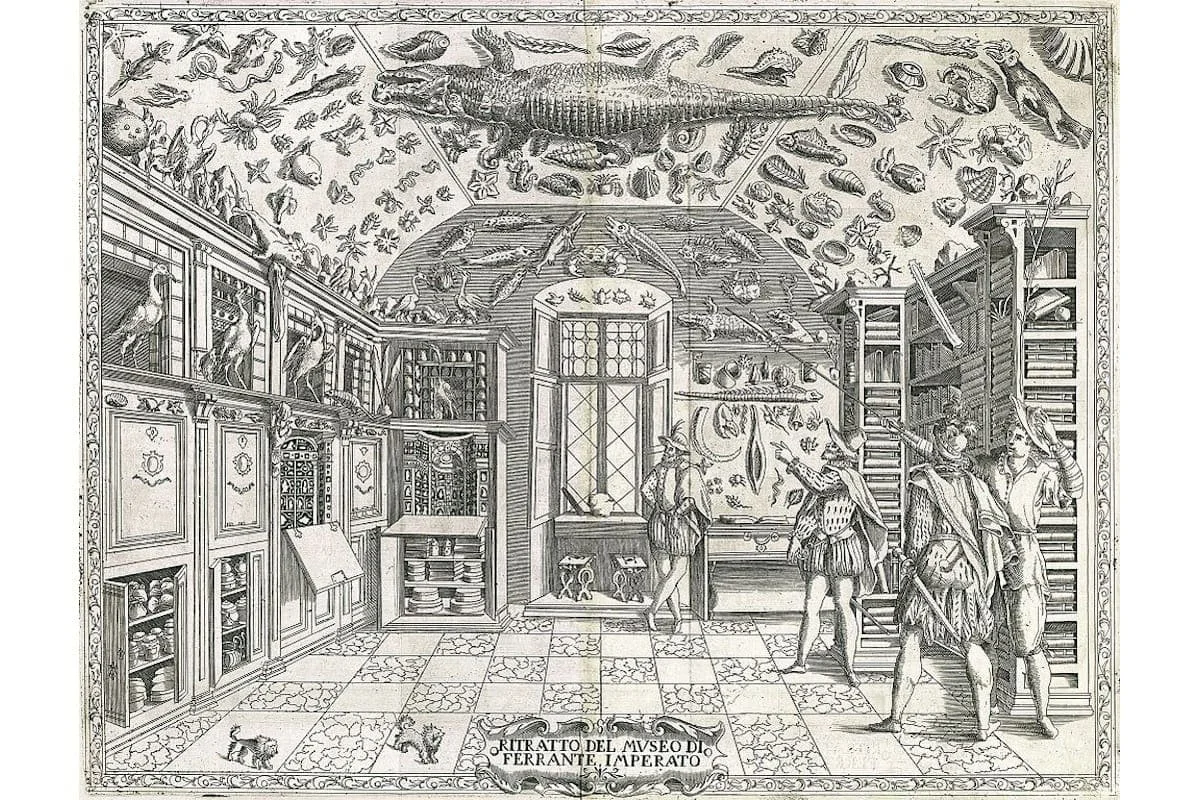

In earlier centuries a ‘Wunderkammer’ was an eclectic collection of art and objects gathered from all over the world and assembled together in displays meant to both impress and educate observers, often in the homes of the wealthy and well-traveled. Troves of curios curated by eccentric collectors guided only by an untethered hunger for the strange. These collections would contain things such as the skeletons of rare creatures, bizarre flora, unreadable codices. In a time before technology enabled the spread of visual information, these ‘wonder-rooms’ were encyclopedias brought to life, tangible presentations of things that many people had only read about or heard of second-hand. Manifestations of man’s capacity for wonder and his infinite fascination with the unknown. Wunderkammers are often regarded as the precursors to modern day museums, and Britain’s oldest museum, the Ashmolean, was founded by Oxford university to house a donated Wunderkammer.

Wunderkammer of Ferrante Imperato, Naples Italy, 1559

One can imagine the impact that such staggering displays of exotica/esoterica had on people not often exposed to foreign sights. Imagine the thrill of being land-locked and having all the secrets of the sea assembled before you like a strange harvest: the novelty of a narwal’s horn, the patina of shipwrecked gold, the alien texture of coral. Imagine never having seen a travel brochure and peering upon a vase pulled from a pharaoh’s tomb, or the skull of a beast you only half-believe in. Imagine how these sights would resonate within your mind like echoes of the unknown. Dodo beaks, magician’s rings, pickled eyeballs floating in jars. The mystery of books written in languages no one can read. These wonder-rooms were things part reliquary and part junk-drawer, a circus crammed within a closet, adorned with all the colors and charms of a Gypsy caravan.

The room I have wandered into here in Franklin possesses the spirit of a Wunderkammer, and much of its contents would not have felt out of place in one. It is part catalog and part kaleidoscope, an array of natralia and cultural curios assembled from all over the world. The artifacts within the cases seem the product of both scientific investigation and compulsive accumulation, and I cannot tell whether I am in the laboratory of a lapidarist or the basement of a mad packrat, and I do not care. Everywhere I look, wonders abound.

There are arrowheads, stone pipes, carved walrus tusks. There are more types of gems and minerals than I have ever seen before or even recognize: quartz, amethysts, crystals. Green globes of malachite and blue orbs of lapis-luzi, brown swirls of Tiger’s Eye. There is Snowflake Obsidian that looks like petals of ice strewn across the surface of a black and bottomless pool, next to the deep green of Chinese Writing Stone patched with shards of lighter color. There is black marble and pink marble and the violet of a Brazilian Amethyst. There is olive-colored moldavite, the gemstone from the stars.

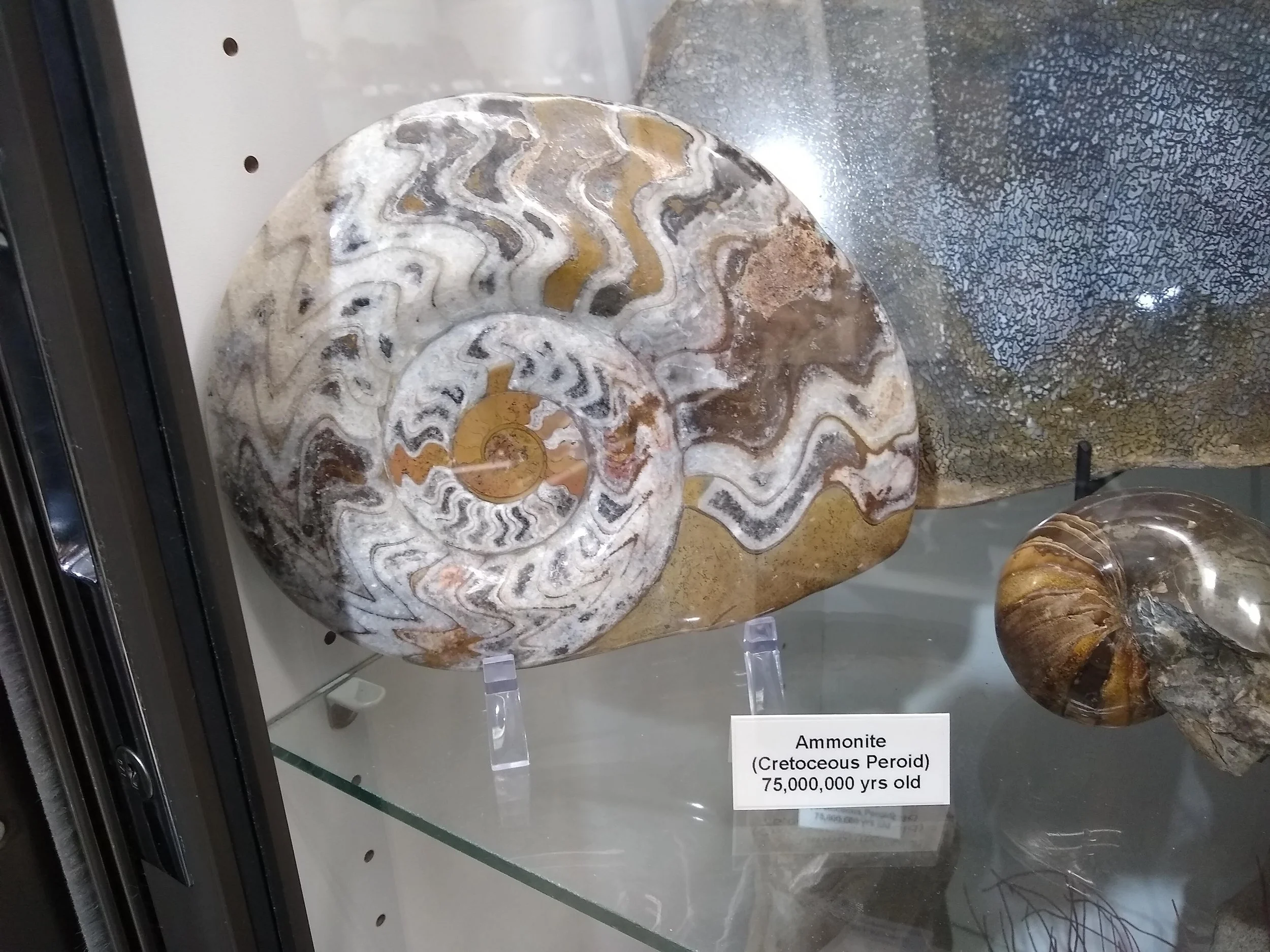

Fossils fill many shelves, just as varied and interesting as the minerals. There is a cast of a Tyrannosaurus mandible and a folded fish fossil. There is a slab of petrified dyno poo that is a golden coppery hue covered in a galaxy of clam-shaped splotches of color which are absolutely beautiful. There is a white-line collage of fossilized ferns on a page of gray granite.

In a small, dark room to the side separated by a heavy curtain there is a case filled with fluorescent minerals. When the ultra-violet lamp above the minerals is turned on they glow neon shades of slime green and ember orange amid sour hues of purple and pink and pale yellow. I stand alone in the darkness peering into their case as though into the terrarium of some unusual creature. The minerals are bright and sickly, like wildflowers that have grown up from the toxic waste of a nuclear sewer, a bizarre bloom of mutant color.

Cultural tokens from all over the world share space with the stones on the shelves. In a case of pre-columbian artifacts there is a tiny copper mask and bola weights, and prehistoric surgery tools made of obsidian. There are soapstone carvings of laughing old men and carved Amber elephants and little vials of engraved Jade.

In a case devoted entirely to carved Ivory there are curved statues of shamanic figures and carved whale teeth bigger than my hand. Antique Ivory billiard balls with crack-like clusters of gray color rest beside a caravan of carved elephants descending in size, the smallest no bigger than a pea.

Each item is a wonder of craftsmanship I could spend hours looking at, but one in particular entrances me. It is a statue of fourteen balls all carved from the same piece of Ivory. The main ball is maybe the size of a baseball, and held aloft on the trunks of three miniature elephants. The other thirteen balls are inside of the first, each one carved somehow within the larger balls. Through small openings you can see sections of the balls within. I look closer and notice that the elegant, lace-like designs I took to be abstract ripples are actually dragons! It has all the intricate interconnectedness of clockwork gears combined with the madness of shrinking space. It is like a descending staircase that goes inward instead of down.

By far the strangest item in the entire strange collection is an actual shrunken head sitting in a side-case in the main room. I have always wanted to see one. It is about the size of a doll’s head, and the skin looks gray and hard. Its eyes are closed and its mouth is sewn shut with ragged strings that dangle down from black lips. It still has its hair. It is ghastly and fascinating with true witch-doctor weirdness.

It is an amazing collection of curiosities, oddities and artifacts, not at all what I would have expected from the basement of a gemstone gift-shop. I spend over two hours in this hidden cabinet of colors and shapes surrounded by splinters of a hundred different ages, the history of a hundred worlds preserved behind glass.

I am both glad and surprised to have stumbled upon this marvelous little hole-in-the wall, and as I leave the basement museum and step back out into the sunlight I think that one way to conceptualize the Appalachian Trail is as an inverted Wunderkammer. Rather than accumulating a variety of exotic objects and assembling them together in a room or cabinet, the A.T. calls one out of the confined spaces of familiar life and into experiences that would not otherwise be had, takes you to places not otherwise ventured to. It is a contrivance intended to force the one experiencing it outward into a larger space, rather than one intended to gather far-flung objects together in front of them. A mechanism of exposure propelling one outward into the world, guiding them toward discomfort and revelation. A wonder-path.

It seems that for many people today life has become a quagmire of constant viewing experiences wherein they are reduced to a passive spectator, a consciousness anesthetized by entertainment and over-saturated with artificial images. Perhaps in this environment the A.T. functions in the same way the curiosity-cabinets of old once did, allowing people to confront the parts of life that exist outside of their normal spheres, A call to adventure bidding them into the world beyond the borders of a screen. A manifestation of the need for wonder and exposure to the unknown that the man of today shares with all of those who came before him.